(published July 21, 2005)

[Continued from Notes from the Giant Squid: Concerning the Governance of These United States, A Primer (pt. 3), PMjA Issue #233]

I gazed at George Double-Yew Bush, seated legs akimbo in his submerged watertight Cabinet, as my great girth was floating just above my grand and waterlogged desk in the Ovoid Office.

George Double-Yew shook the shaggy mane of his head, slumped of his shoulder, and momentarily was silent. Then, with a deep and pitiful gasp of the oxygen in his chamber (lungs to this day amaze me with their inefficiencies), he spoke, saying, "I been wanting to talk to you about these zombie judges, too—"

"Excellent well, George Double-Yew! Let us put aside both our fussing and our the fighting, so that we can get down to a more serious business; with the demise of Willie Rhine-Quest—back to his Fatherland, I presume he roams—"

"Rehnquist died!"

"Sadly," I nodded of the head sac, my optically perfect eyes fixed upon the saggy mammal, "Upon the operating table. I did my best but . . . well, I was hardly aware that humans, unlike any rational animal, are unable to regenerate limbs in a timely manner. And only one heart? It is no wonder that you conservative gruntchimps so lack of the compassion, with only a single heart beating. That is why," I sagely opined, "you can only think of yourselves: One heart. We squid, with three hearts, can care for ourselves, our extensive territorial landholds, and our most fondly regarded athletes. I myself am fond of the Sandy Cow Fax, despite his gay jewdification."

"Adjudication of Sandy Koufax? You're gonna make a sixty-year-old ball player a Supreme Court Justice? I mean, he's a good southpaw, but he ain't no "Whizzer" White!"

"That is verily the problem at hand! I know not how to make the Judicial Zombie! I may be a terrible and ineluctable force Risen from the Deep, but I am hardly a dark and sinister being from a dimension beyond time, possessed of arcane, esoteric, occult and cyclopean powers. With Justice Rhine-Quest, I imagined I would fall back on the old human crutch, technology. Lacking the habilidad to forge a zombie-in-fact, I would simply make the most tenable ersatz-zombie which I might: A cyborg. But it was all for naught," at this admission, I myself did slump with defeats.

"You killed Justice Rehnquist," George Double-Yew declaimed flatly, "tryin' to, like, robotize him?"

"He was already dying," I explained plaintively, "I sought to save him unto eternal undeath, so that he might spend the eternity as he ought, hunting down naughty and unconstitutional Jude Laws and tearing them asunder."

George Double-Yew was silent for a moment, "Damn," he muttered. Then looking up, earnestly, into my all-seeing eye, "Was the funeral nice? Is he in Arlington?"

"There were no funerary rites, as there could be no interment."

"No interment?"

"No body, properly speaking. Yes, much of his torso is available for burial—or was, before that pesky Mr. Mugabe got a hold of it!—but the head, spine, arms and left leg are still at large."

"At large? He's torn apart? Was there one of them suicide bombs?"

To this I took offense, as any craftsman might when his work is so casually derided, "Not torn apart, but rather stitched together, along with his chrome carapace. I sought a more rational form for his eternal unlife, and so fashioned him into a crab of sorts—a land crab, which are assuredly the finest sorts of crabs for lawyers to become—with meat legs and steel legs and a wonderful, judicious head. But alas, my clockwork pumps for the pacemaking and fluid regulation were miscalibrated, and the brain suffered damage and descended into drooling, slack-jawed insensate madness. The autonomic systems remained functional, the would-be cyborg scuttered off, and now terrorizes the greater Washingtonia Area, like and unto the BeltWay Sniper of days of yore, but less of the projectile flinging, and more of the dropping from trees and tearing apart joggers, dog-walkers and lonely wanderers, be they Bills of the Clin-tone, Jude Laws, or neither."

"Does he still have thyroid cancer?"

"One can only hope," I sighed, "For otherwise, he is an unstoppable killing machine. Except for the unborn zygotes, whom I presume he continues staunchly to oppose the destruction of."

"This is terrible," George Double-Yew gasped, the wünderstruck unbelief clear upon his unmuddled, simian brow.

"Indeed! My line-up is two batters short, and—"

"And so you want Sandy Koufa—wait, wait—Hold up, Squidgy. Two. Two. You've killed two Supreme Court Justices?"

"I have killed no Supreme Court Justices: One I have liberated from the daily stresses of sensate thought and mortality, the other retired, of her own accord, to spend time with her spousish life partner, who I believe is male."

"Retired? Who retired" Ruth Badder-Whatsit?"

"Not at all! It was Sandraday, grandchild of Connor."

"Well, don't that beat all," George Double-Yew silently reflected briefly, "She was a heck of a gal; not too shabby for a ranch girl from Arizona."

I crooked a tentacle supercillisouly, " 'Heck of a gal', George Double-Yew? 'None too shabby', George Double-Yew? She was the first Female to serve Supremely on your Court. She graduated at the tipping top of her StandFord Lawyering Class. Forbes (either the magazine or the Steve, I know not which) declared her the sixth most powerful female human in the world—I trust one such as Cheryl Anderson must be in the top three. The most powerful, I imagine, to be some lawyering, industry captaining gargantua with 40 inch pectorals who can deadlift 350 pounds in standard gravity—which is just 58 Moon pounds, but a whopping one-and-one-quarter dog-tons!"

"What are you talking about?"

"Sandraday of O'Connor! You term her a heckuva gal, and I point out that she was highly accomplished in her field, and as a member of her gender, while you were not the first president, nor the first male president, nor the first white male president, nor even the first white male Bush president! Respects are due! You must give unto her the rightful props!"

George Double-Yew's face tensed, gathering itself into a petulant fist, and then relaxed like a sphincter whose work has been performed, "You're right. You're right. I'm sorry; of all the folks around, Sandra is a great gal, and certainly my better."

"Indeed."

"'Course," he smiled wryly, "I'm not doin' too shabby for a failed oilman and C student."

"Indeed, for you are the most favored holding in the Presidential Menagerie of the most powerful cephalopod to ever walk the earth."

At this, he scowled.

"Did I mention that Sandra-Day also dated William Rhine-Quest when they were school chums?"

"Really?"

"Indeed. Now, to the zombification: Right now there are irresponsible and unfeasible Jude Laws roaming this nation at large, and none to put a check upon their balance. How might I zombify Sandra Day so that she might board her little ship of the state and head forth to bring a greater Justice?"

"There aren't any zombies—"

"I know! Such is the problem—"

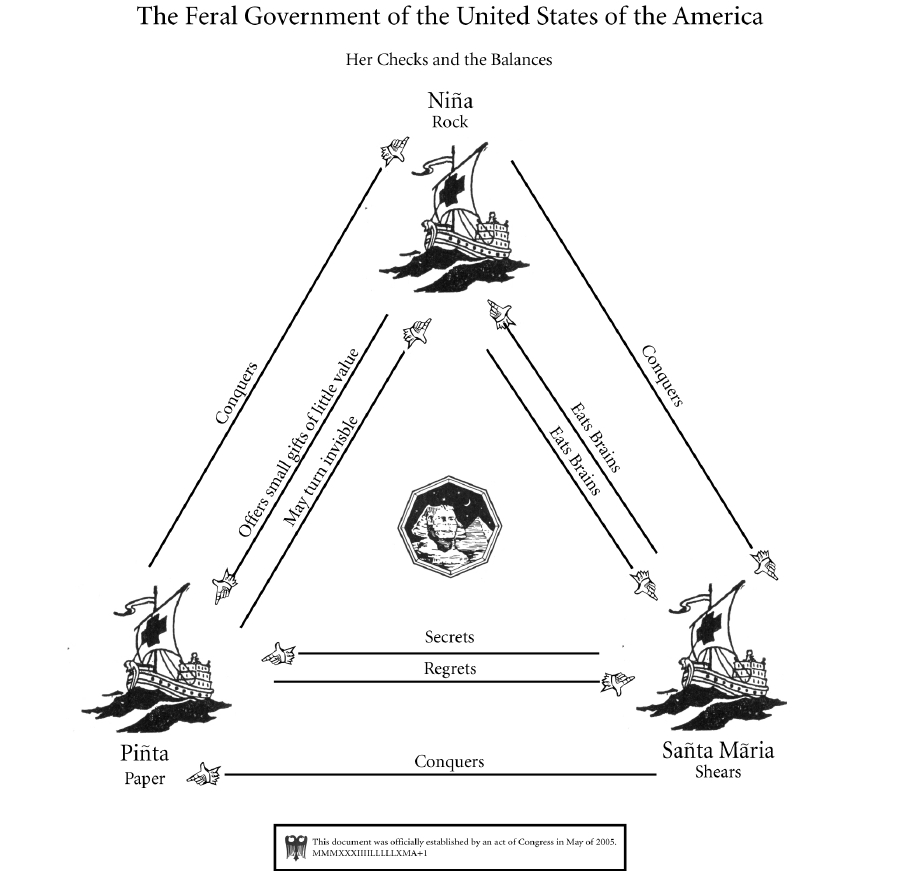

"At All," George Double-Yew barked. Then, calmer, "There's no Zombie Branch of the American government. See, OK, you remember how I explained about how there weren't no Pirates and Pilgrims—get the diagram again," I pressed said diagram to his glass looky-hole:

"See, the thing that really happens here," He indicated my diagram's topmost vertex, "Is Congress: they make bills—not fellas named 'Bill,' but pieces of paper outlining possible law ideas—into 'Laws'—which isn't Jude Law, or any person, just a piece of paper, with a rule on it. This here," he pointed to the lower left vertex, where sets the Piñta with its Indian Ninjan, "Is the Executive Branch, with the President at the top. They make the laws happen. And this," he indicated my lone zombie, the third and final vertex of my Triangle of Good Governance, "Is the Judicial, I guess; Judicial's what's missing, anyway. They decide how regular Americans can work out their problems, and make sure crooks get punished, and decide if the laws are lawful once folks are arrested for 'em. Like in the Bible.

"You also got the checks and balances," he said, indicating the many and several arrows which trace their path among my triangle's points, "With this rock, paper, scissors business, and all of these, these things, secrets and gifts and regrets and such . . . that's all wrong—"

I may have possibly glowered somewhat at this, as I was savagely beating the top of his Cabinet with my arms numbers four through seven. My hunting tentacles—far stronger than my other appendages (save one)—wrapped around his submersible cabinet and began squeezing. A sound not unlike fiberglass splintering pinged through my office.

"—and somewhat over, um . . .," his voice shook madly, "Wrong in that it's overly . . . artful in it's delivery. Simply put, the checks and balances are like this," he pulled from his window momentarily to a-rustle, and then pressed to the hole a diagram, triangular, scrawled upon some printed broadsheet. "See, Checks and Balances; each of the three parts are balanced 'cause they have a check on each other's power: The Legislature makes laws, but the Executive gets to decide if he's gonna veto 'em or not. The President gets to put whoever he wants into the executive roles, but Congress gets to approve 'em or not. The Judicials get to decide what laws are Constitutional, but the President gets to nominate them, and Congress approves that nomination. See, it's all tangled together."

"Like man, wife and child, each with a hand around the other's throat?"

"I . . . well, sorta. Yeah." He shivered, "Yeah."

"And this," I made the air-quotes with the tips of my razor-suckered tentacles, " 'Judiciary Branch', they are made by the Presidente?"

"Appointed, yeah."

"And they go about, slaying Laws as they see fit?"

"Not 'xactley. They can't just go after any old law. They wait until a case comes up, from a lower court, and then decide on if the laws in question are Constitutional or not—if they're in line with what the Founding Fathers—"

"George Washington-Carver?" I barked excitedly, he being my president historical most favorite..

"Yeah, and the others, too. Jefferson and Lincoln and, um . . . Franklin."

"No, his . . . Cousin? Ben Franklin Pierce. Son? Somethin'. But, the Courts, they don't just go willy-nilly messing with laws; they only get to monkey with the ones that come before them."

"The Jude Laws are brought forward by courts of minion-judges? Servants of the Supreme? And it is my presidential honor and duty to make these Courts of Justices."

"Yes."

"How?"

"Well, you pick a judge you like—see, it can't just be anyone. It can't be Sandy Koufax, who was a heckuva south-paw, but isn't a lawyer. Ya gotta pick a judge, and then you nominate him. There's a form. You fill it out, and then it goes down to Congress and they bicker about it."

"And then?"

"Well, then, provided they aren't tied up in their filibuster crap and the fella actually gets a straight up or down vote, they either reject him and you try another, or they accept him."

"And then the zombification? In the dark of the night? How is that right executed?"

"There's no zombies! Just regular old lawyers who've been judges."

"Poppies the cock! You are to tell me that a government founded by melungians, freemasons and wig-wearing know nothings, and cast from the blood, sweat and tears of a million displaced voudon West African slaves employs not a single zombie?"

"Now, you've got it all wrong again, with your cockamamey business. I'm not generally . . . inclined to agree with that halfwit hairball assistant of yours, but it is true that you're really a piece of work, when it comes to explaining things to you. See, you come in with this whole cockamamey explanation of how our government works, and then we're going through, and I'm explaining what you've got a little off on, and none of it's getting through."

I nodded of the headsac in mock sagery, "Yes, I see it all clearly now, George Double-Yew." Thoughtfully I relaxed my constriction of his dwelling-chamber, and stroked the "chin" of my headsac.

"Thank God," he said, releasing a great sigh of the relief.

"I see through your subterfuges. Who is being a naïf now? Look upon the portraits of John Blair, Bushrod Washington, John Marshall, and Alfred Moore; I do not know that zombie is the appropriate term, George Double-Yew, but a simple glance at these pale visages reveals even to the larval human that they clearly be in possession of unholy hungers, hungers not human: George Washington-Carver begat John Blair through dark art, as did John Sam Quincy Adams for Bushrod Washington and John Marshall, and Quincy Sam John Adams all over Alfred Moore's succulent visage. Now, I desire to do likewise, and you will tell me how, cocka-mammeries or no!"

"It isn't possible," he shouted, "There are no goddamn zombies!"

"These are the soured grapes, George Double-Yew!" I pointed with my tentacle, acusationally, "You are angered for, in your four years of infamy you zombified not even one Justice Supreme, and I shall now make two, a zombie groom and bride, king and queen. More zombies shall they make—through arts blackest and processes both biological and heinous—until the fabled zombocalypse is nigh upon us. Tell me! Tell me now!"

George Double-Yew let out a deep sigh of resignation; finally, we'd reached the heart of the matter. "You've got me. It's sour grapes, alright. But, I don't know the . . . formula. It's . . . written down . . . in . . . that's on . . . It's encoded, cryptified on Lincoln's Monument—"

"No!" I gasped, my triple-hearts each tripling their pace to a gallop at the mention of my old nemesis, the Stony Avatar of the Spider God himself, Abram Lincoln!, "mon dieu, it cannot be!"

George Double-Yew was wide-eyed at my response, struck dumb by the swirl of fear-colors coursing over my skin, and then he relaxed, and his face went sage, even sagacious, "Yep; gonna have to go right on up to ole Abe and get it off the plaques and such. And, only a President can do it, only the fella that's to do the zombification. Can't send your aid, or that assistant, or what have you. Lincoln would just, uh, eat them or somethin'. Gobble 'em right up with his stony lips. President's gotta do his own dirty work."

Gentle citizen readers, you cannot guess at nor imagine the pain that then gripped me: More than anything, I did and do want to be a fair and just president, an excellent and exemplary president. But, truthfully told, I had only but barely beaten Abram Lincoln upon our first meeting, and I could not stomach the notion of a re-match. These days presidential have been far from salad days; I have grown somewhat slothful in my habits. If, in my top form, I had barely the strength to conquer—but briefly—Lincoln's stone earth-form, how might I possible face it again, weakened by time and worry and—I shame to admit—the laziness of Public Office. Had I tearing ducts, in that moment I doubtless would have succumbed to the hot, salty succor of tears.

"What am I to do, George Double-Yew!" I moaned, "I cannot face the Lincoln Spider God again—"

"Of course not," he commiserated, "Lincoln is . . . too much for any ma—squid. President. Too much for any president to bear . . . twice. That's why I never had any, er, judicial zombies. Couldn't take Lincoln."

"—and I cannot let the Court of Supreme Justice languish, shy two zombies of the required nonuplet. This life presidential, she is so complex; on every side there are the decisions like a blade not simply double edged, but double sided—a blade with a blade for a handle, and no matter how she is lifted, you are cut to the quick."

"A hard life," he agreed, "a damn hard life."

I was given to despair.

And it was in that moment that George Double-Yew, dear George Double-Yew, came as saviour and slew the dragoon that had set upon me, nostrils a flame, and nickers savage and tearing.

"Squidgy, let me ask you: what was your favorite part of being a regular citizen?"

I thought upon this, the question having come from the proverbial field, such as where Sandy the Cow Fax does his south-pawed switch-hitting for both teams.

"Once," I began slowly, "I was exploring in the sewers of Detroit—it was near upon the Fourth of July—and I looked up through the storm drains of the Jefferson Ave, and saw that the fireworks, traditionally shared among the Detroit and the Windsor canadianados on or about the end of June, were working their fire upon the sky. It is a great and terrible display; as it builds to climax the sky is filed with phospheresence of burning magnesium, iron and copper, and night is made day again. The thunder of reports forces the buildings to sway, and shakes loose grit and rubble down from the sewer tunnel tops. I looked, upon the sky, and upon the curved, glassy face of my own Renaissance Center, from whose top I once spied down upon the world anonymous, watchful, and those sparks and flames in the sky, reflected in the mirrored glass, became a sea and cataract of fire pouring down, ceaseless, endless, upon the people, as our own good fortune and grace as Americans does always pour down upon and among us. Shifting but slightly in the sewer, I could see the faces of the spectators. Detroit is a city sparsely populated, and almost exclusively of blacks and blackness, but for the works of fire, the city repopulates with its failed and extinct diversity: out from the suburbs and exurbs and anti-urbs they pour, to return to their source like salmons. In the crowd there is blackness and browness and pinkness and paleness and a mellowness of hue, a diversity—in dress and decoration and modification and comporture—liken to challenge that of a squid's hueful hide, all lit by the tamed savage spark and fire of human ingenuity wrought upon the blameless, open, searingly waterless sky. It was, by far, the most beautiful sight I had seen, and I have seen things—beyond time and space and notion and word—I have seen things whose beauty would stop your single, quad-chambered blood pump with their Glory. But those simple, simian faces lit by spark and fire and glory and pride and humanness and togetherness; even alone, in the sewer, watching as an alien to those festivities, I could feel the warmth of their human togetherness, of their shared exposure to that terrible ersatz war they enacted against the sky itself, against the homeland of the God they imagine watches over them, but who really exists not, and the closest helpmate, husband and protector, he watches up from beneath, from their sewer tunnels, and is benefactor but, sadly, no god."

"And so your favorite part?" he asked, his face bearing the unmistakable stamp of slight befuddlement.

"Serving my fellow citizens, as advisor and consort."

"See, my favorite part of being a citizen was being out alone, on my ranch, shoveling and mending fences and such. A president has to go out and recharge often. You've been in office half a year with no break. You need your recharge, buddy."

"You're right."

"You need to head out, help your fellow man and such. Get hands on."

"Yes!"

"And while you're gone— see, I've been a president, I've faced Lincoln before and learned a lot from our lil tussle. So I think I can go and brave ole Abe, and get your zombies together—I can take care of all of this while you're gone to see the people—"

"YES!"

"You're where I can't see you," George Double-Yew called from his oaken cask, as I shot back behind it, "It makes me nervous when I can't see you, Squidgy. What are you up to? Not a baboon again?!? Please!" He banged upon the sides of his cask as I slipped into my environmental suit, slipped the surly, mothering, lulling and nullifying grasp of the water into my clumsy perambulatal autokineticon.

"Please don't do anything rash!" he banged, "Or weird! Please!"

And then I pulled the scuttles on my Oval Office, and the sound of thousands of gallons of water escaping was unmistakable, and drowned out whatever further mock beggary George Double-Yew engaged in—such the little clown!

"In my absence, George Double-Yew," I shouted, "Care for all as would I! Let Sang check his dials! Follow Molly's direction! Ignore Rob! Beware of Mr. Mugabe!"

And the last of the waters sluiced away, and I threw open the frenched doors to my Rose Garden. It was night, and the night came into the waterless room, and I went out, into the night, into America. As I leapt the wrought iron fence, into the shriek of traffic on the Pennsylvania Avenue and down the midnight streets, I thought I could hear the arachnid, articulated whine of Just Us Rhine-Quest creeping through the trees of the National Arboretum, and my dear George Double-Yew tapping at the inside of his Cabinet, requesting some aid, and all of America breathing in its restless sleep, hoping soon one would come to lend aid and succor.

And that one was to be me.

THE END of "Notes from the Giant Squid: Concerning the Governance of These United States, A Primer"

or check the Squid FAQ

Love the Giant Squid? Buy his first book.

Share on Facebook

![]() Tweet about this Piece

Tweet about this Piece

Squid Archives